The History Of The Hollies

Reproduced from Goldmine, an American Record & CD Collecting magazine.

July 5, 1996. Volume 22 - No 14 - Issue 416

Introduction

When the book on British Invasion rock 'n' roll is finally closed--which, one suspects, may not happen until Mick Jagger and Keith Richards depart the concert stage in wheelchairs--someone may just take a long look at the deserving acts that didn't make it to fame and fortune in the United States.

When the book on British Invasion rock 'n' roll is finally closed--which, one suspects, may not happen until Mick Jagger and Keith Richards depart the concert stage in wheelchairs--someone may just take a long look at the deserving acts that didn't make it to fame and fortune in the United States.

Maybe somewhere, someone will take a look at the most under-appreciated of all successful British Invasion acts: The Hollies.

Calling The Hollies under-appreciated may seem surprising to anyone who has passed through a record store lately and seen the two hits anthologies from Epic Records, the triple-CD anthology from EMI, the CDs of two of their early-1970s albums, and upwards of a half-dozen overlapping low-priced reissues, intended for the bargain bins. Add on a dozen or so imports from England and elsewhere, devoted to their music from 1964 through the end of the 1970s, and it seems like The Hollies are reasonably well-recognized as a successful band of the 1960s and 1970s.

And that's true, except that their mass recognition is generally limited (especially in America) to a selection of perhaps a dozen hit songs, from 1964's "Just One Look" up through 1976's "The Air That I Breathe." In reality, their recorded history started in 1963 and encompasses more than 350 songs, spread over dozens of albums, EPs and singles, across 33 years. And the band continues to perform to significant audiences all over Europe in the 1990s, and began 1996 with a new release on MCA, one that puts them in effective "collaboration" with the late Buddy Holly, in a re-dubbed version of the latter's "Peggy Sue Got Married.

Small Beginnings

Small Beginnings

Like a lot of long-lived creative endeavors, The Hollies' history began by chance, in this case, five-year-old Allan Clarke's arrival as a new student one day at the Ordsall Primary School in Manchester, England in 1947.

Harold Allan Clarke was born April 5, 1942 in Salford, one of six children. He made the acquaintance of five-year-old Graham Nash (born February 2, 1942) on his first day at school, when Nash was the only student to volunteer to let Clarke sit next to him in class. The two became friends then and there, and it turned out that one of the interests they shared was music. They both sang in choir, joining their voices together for the first time in "The Lord Is My Shepherd," and it was from there that the notion of their singing together took root. They found that, even as they matured, their voices complemented each other magnificently. Unfortunately, there was no such thing as rock 'n' roll at the time, and their spontaneous musical efforts together didn't begin until the 1950s.

In 1956, everything changed, as rock 'n' roll began to trickle in to England from America, but the immediate impetus for Clarke and Nash to begin music careers together lay in the birth of skiffle music, with Lonnie Donegan and his version of "Rock Island Line," and its various follow-ups.

"We didn't know what hit when skiffle came along," Clarke observed. "We all wanted to be rock 'n' roll stars, and skiffle was one way to start, because it was all based on the easiest chords to play, A, D, G, and C, and we loved the songs. Graham and I played clubs in Manchester, doing an Everly Brothers-type thing. The Everly Brothers were our real inspiration, because of the two-part harmonies."

They worked under a variety of names, including the Two Teens and the Levins. The Levins, in particular, symbolized important breakthroughs in Clarke's mind, at least at the time, because the name was derived from the brand of guitars they were using, and simply having a brand of guitar that didn't make one ashamed was progress. "The Levins were named after my first jumbo guitar. I was very pleased with that at the time," he recalled in a 1996 interview.

With help from their families, Clarke and Nash purchased Guytone guitars, and re-christened themselves the Guytones, which later became the Fourtones.

Clarke and Nash played any place that anyone would listen to them, and this included a performance at the legendary Two I's coffee bar in London, where acts such as Tommy Steele and the Vipers (featuring future Shadows lead guitarist Hank B. Marvin) were discovered, and Cliff Richard played and sang. "It was years and years and years before we were a group," Clarke recalled of the Two I's, adding that it had little mystique for him, being a miserably tiny little place compared to locales such as the Cavern in Liverpool.

At one point, when it seemed like sibling acts such as the Everly Brothers were the coming thing, Clarke and Nash billed themselves as Ricky and Dane Young (Clarke was Ricky and Nash was Dane), hoping to be taken for a brother act. Such strategies would work better for real-life and fake siblings alike, such as the Brook Brothers and the Walker Brothers, not to mention the Righteous Brothers. But the Ricky and Dane Young gambit paid off, getting them hooked up for a time with a local Manchester band called the Fourtones, whose membership included Derek Quinn, later of Freddie and the Dreamers.

It was while they were playing a gig with the Fourtones that Clarke and Nash were approached by Eric Haydock (born Feb. 3, 1943), the bassist for a group called the Deltas, and invited to join his band. After abandoning the Fourtones, they took up Haydock's offer and signed aboard his band. The Deltas were a large ensemble group whose stage act included novelty songs and costume changes, none of which seemed to offer much of a future in the band scene as it was developing in Manchester and other points north.

It was while they were playing a gig with the Fourtones that Clarke and Nash were approached by Eric Haydock (born Feb. 3, 1943), the bassist for a group called the Deltas, and invited to join his band. After abandoning the Fourtones, they took up Haydock's offer and signed aboard his band. The Deltas were a large ensemble group whose stage act included novelty songs and costume changes, none of which seemed to offer much of a future in the band scene as it was developing in Manchester and other points north.

Following a few membership and repertory changes, the Deltas provided the nucleus around which The Hollies formed. The new group, not yet named, featured Allan Clarke on lead vocals, Graham Nash on rhythm guitar and vocals, Eric Haydock on bass (rather unusually, a six-string model, incidentally, as opposed to the usual four), Vic Steele on lead guitar and Don Rathbone on drums.

How the new band got its name has been a subject of conjecture for decades, and stories are sufficiently vague to convince one that not even the band members remember exactly.

The conventional assumption for many years was that Hollies was chosen as a tribute to Buddy Holly, in much the same manner that the Beatles chose their name as a sort of acknowledgment of the Crickets. But the truth was little more uncertain.

The group members all admired Buddy Holly, to be sure, as did virtually every rock 'n' roller in England during this period. But the most likely reason for the choice of the name The Hollies was pure expediency and sheer luck, not admiration of Buddy Holly. According to one oft-told story which seems to have the kernel of truth within it, the group had been assembled out of the Deltas at the end of 1962, as the holidays were approaching, and were busy trying to decide upon a name in a room that happened to be heavily decorated with, among other Christmas-related accoutrements, holly. The band name followed, initially as a stop-gap, and it's stuck for 34 years and counting.

The band's first gig as The Hollies took place at the Oasis Club in Manchester in December 1962, and was a great success. Not long after, the Beatles graduated from the Cavern Club, having been signed to EMI's Parlophone label by producer George Martin, and soon after, The Hollies took their place at the most celebrated music venue in all of England.

At the time, the Liverpool quartet had barely scraped the charts with their debut single, "Love Me Do," but something was in the air in the north of England. The amount of musical activity in Liverpool and Manchester, coupled with the mere fact that Parlophone, a tiny label in the EMI family scarcely known for its acumen with popular music (the label's biggest releases until then were comedy records by Peter Sellers and Bernard Cribbins), had reached the Top 20 with a song by a Liverpool band, caused record producers who'd previously never ventured very far from London to start looking to the north.

One of them was Ron Richards, a staff producer at EMI, who went up to the Cavern in January 1963, just a few weeks after The Hollies were formed and shortly after they'd taken over the Beatles' spot at the Cavern, playing the mid-day shows. What he found was a tiny club that lived up (or down) to its name, packed to the rafters with teenagers jammed in as tight as they could, listening to this group wail away.

He also found that The Hollies could do more than just wail. They played fast and hard, because one just didn't compete in that environment without doing that--Richards was especially impressed with the furious manner in which Graham Nash attacked the fretboard on his guitar, until he learned that there were no strings on the instrument--but so did a lot of other bands on the Liverpool scene. Indeed, groups such as the Big Three, a northern power trio that held their fans in awe for a time, were considered far more formidable musically than either the Beatles or The Hollies.

But The Hollies, like the Beatles, the Searchers and a relative handful of bands working in those days, could also sing--and, like the Beatles, the Searchers et al, The Hollies could do more than just thump out a song with a pile-driver beat if that was what was needed. And as record producers soon discovered, that was exactly what was needed to put these acts over on record, as opposed to the clubs. Clarke and Nash could sing, and they could harmonize together, and the seemed to offer the possibility that they might be able to move beyond the American rock 'n' roll standards that they were learning off of the original records at the time.

Not all of this was necessarily obvious to Richards at the time. What was clear was that the group put on a good show, had charisma on stage, and offered at least as much potential as the Beatles seemed to at the time.

Not all of this was necessarily obvious to Richards at the time. What was clear was that the group put on a good show, had charisma on stage, and offered at least as much potential as the Beatles seemed to at the time.

He invited the group to come to London for an audition for EMI's Parlophone label. The acceptance of this invitation led to the first split in the primordial ranks of The Hollies, as guitarist Vic Steele bowed out, preferring not to turn professional.

The group's manager, Alan Cheetham, began scouting a replacement in one Tony Hicks (born December 16, 1945), who was making a name for himself locally as an ax-man with a band called Ricky Shaw and the Dolphins. The Dolphins' drummer was Bobby Elliott (born December 8, 1941), who would later become the final link in The Hollies' success. At that time, however, Elliott was more concerned with losing a talented band mate to a rival group.

"I remember this guy used to turn up at every gig," he recalled in February 1996, of Cheetham's efforts, "and we knew he was trying to get Tony away from us!"

Tony Hicks was, even then, a guitarist's guitarist, one of the most skilled players in a field filled with many would-be stars but relatively few genuine, viable talents. His own entry into music came by way of skiffle music, which he loved. He was drawn to the guitar early on, and his first instrument, an acoustic model, came to him by the kindness of an aunt who purchased it for him. Early on, he knew what he wanted to do with music and what he wanted to play. This, in turn, only heightened his fixation on American rock 'n' rollers, because they had better players and better guitars than almost anything available in England at the time.

Hicks was born too late to have seen Buddy Holly play in England, but he is old enough to remember the ads for Holly's shows. Holly and other American guitarists, most notably Rick Nelson's lead player, James Burton, fascinated him. "I remember hearing 'Hello Mary Lou,'" he recalled in an interview early in 1996, "and wondering who was playing that wonderful guitar."

In those days, he recalled, this was not a lonely fixation. "Concerts would sell out just because of the guitars that these bands were playing," he remembered. "We would travel to the shows just to get a look at the guitars."

Hicks's first group was a skiffle band named, appropriately enough, Les Skifflelets, which, he recalled, was a bunch of guitars, all playing rhythm, one board and one bass. As with most skiffle bands, the members generally drifted off gradually into other activities as they discovered the limits of their abilities or, as in Hicks's case, they remained in music and began expanding those limits. His own early guitar idols included Big Jim Sullivan, James Burton and Chet Atkins, but not--perhaps not surprisingly, in view of these preferences--Chuck Berry. "I was more into Eddie Cochran," he recalled, of rock 'n' roll's first wave.

Eventually, Hicks's musical sensibilities took him in a very specific direction, through his experience of the legendary English band Johnny Kidd and the Pirates. "I was 14 or 15 when I saw them, playing ballrooms," he remembered of the group, who were responsible for writing and having the first hit with "Shakin' All Over," generally acknowledged as the first piece of genuinely top-grade rock 'n' roll to come out of England. "There was Johnny Kidd, and this three-piece band, and they were just incredible to hear, they played so loud and clean. That was the sound that I wanted on stage--just one guitar, one bass, and drums, with no rhythm guitar in the way."

Ricky Shaw and the Dolphins was a popular local act, and despite Cheetham's entreaties to consider joining The Hollies, Hicks wasn't about to give up a spot in his group to join and band barely 60 days old. At the time, Hicks remembered in an early 1970s interview, the band scene in the north was one of healthy competition, but not necessarily the frenzied rivalries portrayed in the press. "I think it was just good press news to make the north--Liverpool, Manchester and whatever--out to be that. Fierce? I don't know.

"There was competition, inasmuch as there were groups equally as good as each other. There was no jealousy. I must admit that the Liverpool groups come more to mind. As far as Liverpool goes, top of the tree was the Beatles, and then you move down with Gerry and the Pacemakers, Billy J. Kramer and then names that didn't particularly make it, the Remo Four and the Big Three. They stick out in my mind more than Manchester.

"We'd play at the Cavern and just wander out and see the Big Three play, which was just incredible. It was something very new, very exciting. Old amplifiers, no sophisticated stuff. I remember the guitarist with the Big Three [Brian Griffiths] used to go onstage with four strings. He'd go out and play with four strings. They were just rough and ready Liverpool geezers, there for a few pints. And he'd think 'four strings? Fair enough. Better than three, but I'd prefer five or six.'"

Hicks decided to check The Hollies out, and went to one of their shows. He liked what he heard, and was given more to think about when he learned from Graham Nash of Ron Richards's offer of an EMI audition.

Hicks decided to play a rehearsal with the group, and their run-through of a handful of songs satisfied everyone, and he was in the band. The EMI audition took place on April 4, 1963 at EMI's Abbey Road Studio No. 2, which led to three finished songs, a cover of the Coasters' "(Ain't That) Just Like Me," and two originals by Allan Clarke and Graham Nash, "Hey What's Wrong With Me," and "Whole World Over." "(Ain't That) Just Like Me," completed in 10 takes, became the band's debut single, released at the beginning of May 1963 backed with "Hey What's Wrong With Me."

A String of Successes

During the week of May 25, 1963, musical acts of all descriptions occupied the 50 places on the British record charts. The Beatles were at #1 with "From Me To You" and ex-Shadows Jet Harris and Tony Meehan were at #2 with an instrumental entitled "Scarlett O'Hara." Scattered across the rest of the British Top 50 were songs by transplanted Scotsman Johnny Cymbal ("Mr. Bass Mann"), the Springfields ("Island Of Dreams"), featuring Dusty Springfield in her folk music phase, and Sweden's spacesuit-clad rock 'n' roll loonies, the Spotnicks, among others.

During the week of May 25, 1963, musical acts of all descriptions occupied the 50 places on the British record charts. The Beatles were at #1 with "From Me To You" and ex-Shadows Jet Harris and Tony Meehan were at #2 with an instrumental entitled "Scarlett O'Hara." Scattered across the rest of the British Top 50 were songs by transplanted Scotsman Johnny Cymbal ("Mr. Bass Mann"), the Springfields ("Island Of Dreams"), featuring Dusty Springfield in her folk music phase, and Sweden's spacesuit-clad rock 'n' roll loonies, the Spotnicks, among others.

Ensconced some 49 places down from the Beatles' single that same week was Parlophone R5030, "(Ain't That) Just Like Me," a debut recording by The Hollies.

Eventually it would rise to #25, a modest but respectable first showing, and probably comparable to what the Beatles' "Love Me Do" would have done had Brian Epstein not helped cook the record books by purchasing a couple of thousand copies through his NEMS Record Shop.

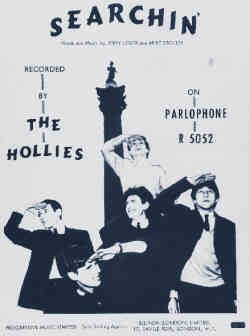

The group followed this up with another Coasters cover, "Searchin'," recorded July 25, 1963 in 13 takes, with one of the band's managers, Tommy Sanderson, playing the piano. It was released the following month, with the B-side, "Whole World Over," another Clarke-Nash original, appropriated from the April 4 session. This record did decidedly better, entering the charts on August 29, 1963, and eventually peaking at #12 in England. Naturally, in this prior to the Beatles' arrival in America, there was no U.S. release of either record, nor any consideration of an American issue. These were records conceived and sold entirely to a local and national market, though by the time of "Searchin'," with the Beatles on their third #1 single, it was becoming clear to everyone that there was real money and fame to be had for musicians from the north of England, at least in England.

It was just after the recording of "Searchin'" that another line-up change in The Hollies took place, as drummer Don Rathbone left the band. "I think Don Rathbone left the band," Clarke said, "because he wasn't that good a drummer, and it was becoming obvious from our recordings."

In a 1974 interview in Melody Maker, Clarke elaborated: "He was good enough for roadwork, but when we got in the studio he just didn't come up to scratch because it showed more on record than it did on stage."

Rathbone, who hailed from Stoke-on-Trent, left the band in the late summer of 1963 to go into management, before leaving the music business. His replacement was virtually waiting in the wings, Hicks's old Dolphins' band mate Bobby Elliott, who had moved on from the Dolphins to playing with Shane Fenton (who later emerged in the 1970s glitter scene as Alvin Stardust) and the Fentones.

The classic Hollies line-up was now in place. Elliott's arrival was more than a little fortuitous, for not only was Elliott--whose personal musical interests went more toward jazz than rock 'n' roll--one of the best drummers on the band scene in the north of England, but he had a good ear for songs and music in general. In later years, when The Hollies were going through musical and membership transitions that left their stage act a little less than tight, his playing would impart a laser-like focus to more than one concert. But more immediately, in the early fall of 1963, his and Tony Hicks's discovery of an old copy of "Stay" by Maurice Williams and the Zodiacs, unearthed at a junk shop in Scotland, gave the band the source for its third single.

The October 11, 1963 session yielded a proper single in only eight takes (the band was getting better in the studio), and the November 1963 release charted immediately and became their first Top 10 success, rising to #8 in England. The B-side was a Clarke-Nash leftover from a May 1963 session with Rathbone still on drums, "Now's The Time."

As a sign of the times, it became their first single to be released in America. By the late fall of 1963, some U.S. record companies were becoming aware that there was something stirring in England that could, although it was unlikely, catch on in America as well. "Stay" was the first Hollies record to benefit from these vague indications of interest in British rock 'n' roll, making its first appearance on this side of the Atlantic in January 1964, courtesy of a contract with Imperial Records negotiated by Ron Richards and Tommy Sanderson.

By that time the Beatles' records were showing up in the States, along with a handful of other British releases. The Hollies' "Stay" was part of that handful, and it never charted in America, a situation with which the group would become familiar over the next year or two. The Hollies' relationship with Imperial would later prove frustrating, but at the time simply getting their records out in America was a breakthrough.

The Hollies' fourth single, "Just One Look," was another cover, this time of an original by American singer Doris Troy that was first heard by the band at a party. "It just stood out as a great song," Tony Hicks remembers. The song was to become the earliest track by The Hollies that most Americans would know.

Recorded on January 27, 1964 and released the following month, "Just One Look" was the record that established The Hollies once and for all as hit-makers, rising to #2 in England. In America, however, it barely scraped the charts, edging to #98 for a week, but the British success was still significant, a breakthrough for the band, and also gave a special benefit to Tony Hicks and Bobby Elliott. Up to this time, all of The Hollies' B-sides had been written by Allan Clarke and Elliott, who benefited as songwriters from the success of the A-side--the authors of a single's B-side collecting royalties on the same basis as the authors of the A-side. For the B-side of "Just One Look," however, at Ron Richards' urging, Hicks and Elliott delivered their one and only collaboration as songwriters, in the form of "Keep Off That Friend Of Mine."

The singing on "Just One Look" was the finest The Hollies had committed to vinyl up to this time, with radiant harmonies and a powerful, soulful lead vocal performance by Clarke, crisp guitar playing, and drumming by Bobby Elliott that also managed to stand out amid all of this activity, with Eric Haydock providing a melodic yet rock solid performance at the bottom of it all on the bass. It was probably the classic, perfect record by the early Hollies, showing them off to best advantage, reshaping an American song in their image. "Keep Off Of That Friend Of Mine," by contrast, didn't reveal Hicks and Elliott as great unheralded songwriting talents, but it did give Hicks one of his best guitar showcases on record from this era.

By this time, The Hollies were firmly established in the front rank of British beat boom bands, with a respectable record of success and a formidable stage act. Clarke's, Nash's and Hicks's voices were among the best in the business, and the instrumental trio of Hicks, Haydock and Elliott was like a steamroller on stage, flattening much of the local competition. A number of their early tours put them alongside acts like the Rolling Stones, where they held their own. By rights, the band should have been a sensation in the press as well, but somehow The Hollies were not accorded the kind of respect and attention that their northern peers--Gerry and the Pacemakers and the Searchers (the Beatles by then having no equals, in terms of success or exposure)--received.

The group's problem was two-fold. The first lay in its image, which was somewhat indistinct--the group's only "gimmick" was its incredible harmonies, which somehow didn't make as good copy as the silly dance steps of their Manchester compatriots Freddie and the Dreamers, or the overbearing cuteness of the likes of Herman's Hermits. And somehow, Searchers spokesperson Chris Curtis was always being printed saying something deemed quotable, and Searchers bassist Tony Jackson was also treated as something of a "star" within the group, while The Hollies were seldom written up at all.

The other problem rested with the way their work was perceived by the more serious critics and listeners. The Hollies were already "suspect" for the prettiness and upbeat nature of their work, which made them seem like nothing more than a pop outfit. They might've gotten past that problem however, if only a successful songwriter or two had emerged from their ranks very early on, as the Beatles had.

But The Hollies' songwriting efforts were confined to the B-sides of their singles, and showed off the limitations of their abilities in this area. As it was, their fifth single, "Here I Go Again," was to feature an original (credited to "Chester Mann," as in Manchester) that had a very high haunt count in its verses and melodies, but it was just not considered enough. And as long as The Hollies specialized in covering established hits from America, they were going to have a credibility problem with more serious critics and listeners.

Their first album, Stay With The Hollies, released in January 1964, the same month that they recorded "Just One Look," consisted entirely of covers and only seemed to exacerbate their problem. The fact that each of their first four singles were covers of American R&B, and two of them specifically songs by the Coasters, had alienated some listeners.

Naturally, all English bands of the era did their own covers of some American R&B, and if all a group was interested in was potential chart action, that was no problem--a record either sold or it didn't. But the Beatles and, even more so, the Rolling Stones and the Animals, succeeded separating the sheep from the goats with their R&B covers. John Lennon's larynx-tearing performance on the Beatles' version of "Twist And Shout," and the group's only slightly less impassioned versions of "Please Mr. Postman," "You've Really Got A Hold On Me" and "Long Tall Sally"; the Stones' cranked-up, high-voltage renderings of Chuck Berry's "Come On" and the Valentinos' "It's All Over Now"; and the Animals' definitive cover of "House Of The Rising Sun" (which they got from a record by Josh White, not Bob Dylan, as has long been reported)--all of these records raised the ante for any other British groups seeking to interpret American songs and get good press for it on top of good sales.

The Hollies got the latter, but not always the former. That dubious arbiter of British taste, Screaming Lord Sutch, reviewing the group's single "Searchin'," in the August 31, 1963 Melody Maker, wrote: "I can't describe how much I hate it. It's a complete muck up of a great R&B thing. Horrible when you know the original. This record is absolutely diabolical. I loathe it and I hope it flops."

Fortunately, the British public didn't share his disdain, and "Searchin'" did sell.

To be taken seriously as well as sell records, however, a band had to do more than just pleasant or lively covers of American songs. To some onlookers, it was unclear at first just what The Hollies were trying to do with their covers, become ballsier competitors to Freddie and the Dreamers, or players in the bigger leagues, alongside the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.

Allan Clarke felt compelled to respond to this in the February 22, 1964 issue of Melody Maker: "[We do covers of American songs] because we like doing them, we think they sound good, and we do them our own way. We're not comparing ourselves with the Coasters but just the same we've done two of their numbers."

More recently, Clarke still maintained, "They were simply good songs, and we did them differently."

Still, the bookings poured in, regardless of the critics, and the band was working harder than ever. In April 1964, the band embarked on a seven-week tour of England booked in support of the Dave Clark 5, then riding the wave of success generated by their early hits.

The group's fifth single, "We're Through," was their first original A-side, written by Allan Clarke, Tony Hicks and Graham Nash under their new collective pseudonym of "L. Ransford." The song garnered a favorable Melody Maker (September 12, 1964) critique from Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, appearing as a guest reviewer in the magazine's "Blind Date" column, in which a celebrity was asked to comment on new recordings without being told whose record it was.

"Liked that guitar run," guitarist Jones remarked of Tony Hicks's playing. "I don't know who it is, but I'm pretty sure it's British. Great guitar solo, very light and pleasant. Not exciting but pleasant. Don't think it's a hit, but it's pleasant. If I were programming Radio Caroline, I'd play it quite a bit."

The mix of voices, especially the placement of the chorus in relation to Clarke's lead vocal, and the different guitar sounds was quite a departure from any of the group's previous records, and if one listens closely to the beat and the rhythm guitar part, one can hear the forerunner of one of the band's most popular and enduring album tracks, "Tell Me To My Face."

"We were in a bossa nova phase at one point," Clarke remembered, when asked about the relationship between the two songs last month. "It just happened we wrote three or four songs with that sort of beat, and 'Tell Me To My Face' and 'We're Through' were two of them."

Recorded on August 25, 1964, "We're Through" was released the following month, paired off with an original B-side, the somewhat harder rocking "Come On Back," and on September 26, 1964, the single entered the British charts at No. 27 and, during a relatively short stay, peaked at #7, a fact that, in the wake of "Just One Look's" #2 showing, discouraged the record company from pursuing any more original A-sides from the band at that time. As an original A-side, however, it was a milestone for the band, and portended better things to come for them.

Recorded on August 25, 1964, "We're Through" was released the following month, paired off with an original B-side, the somewhat harder rocking "Come On Back," and on September 26, 1964, the single entered the British charts at No. 27 and, during a relatively short stay, peaked at #7, a fact that, in the wake of "Just One Look's" #2 showing, discouraged the record company from pursuing any more original A-sides from the band at that time. As an original A-side, however, it was a milestone for the band, and portended better things to come for them.

In January 1965, the group returned to outside sources with a new single, Gerry Goffin and Russ Titelman's "Yes I Will," which was brought to the band's attention by producer Ron Richards from a demo on which Goffin's then wife Carole King was singing. The record, cut in 16 takes on January 3, 1965, had a more elegant sound than their previous singles, with more sophisticated playing and singing. It was strongly reminiscent of the Beatles, the Roulettes and the Merseybeats, except perhaps more elegant in its singing than anything those groups would have achieved. The B-side, the "L. Ransford" original "Nobody," recorded in two takes during a December 15, 1964 session, was a somewhat bluesier than usual number, complete with a dominant harmonica--played by Allan Clarke, who did all of the harp on The Hollies' records--and a raunchy guitar sound for a change.

"We always had a great deal of freedom on the B-sides," Clarke explained. "It was a matter of doing basically whatever we wanted."

"Yes I Will" reached #9 on the British charts, and by this time, it was clear that The Hollies had staying power among the first wave of post-Beatles British Beat bands. Unlike some of the other first wave bands, whose popularity had reached a plateau or begun to recede--or which could only maintain their audience with the heaviest of publicity pushes--The Hollies' audience was not only consolidating but growing, and each single marked a new step forward, an experiment with a slightly different instrumental sound or vocal arrangement. Moreover, they were doing it without a huge amount of publicity--the band was not mentioned much in the music press during those early days.

By the spring of 1964 in England, the shine was beginning to wear off the so-called Merseybeat sound and the bands specializing in it, and it was clear that a lot of groups that had sold records with relatively little effort up to that point were going to face an increasingly competitive musical environment. The Hollies were staying ahead of the curve, continuing to evolve as a recording act, and outclassing their competition onstage. In March 1965, with "Yes I Will" still ensconced at #11 on the charts, the group began its biggest tour of England yet, booked with the Rolling Stones.

Interviewed in Melody Maker on March 27, 1965, Hicks explained the difference between the group's live and studio sound, which mostly involved the guitars. "We don't use a rhythm guitar onstage--we think they blur the sound, get in the way. I'm happy to say a lot of people, including Americans, have complimented us on our clean instrumental sound. I believe this is why."

Indeed, the group's records in some ways sold it short in terms of its sound onstage, which was far more powerful than the singles would have indicated. Onstage, the group resembled acts such as Johnny Kidd and the Pirates, and Screaming Lord Sutch's Savages, as much as it did the Beatles, Hicks's guitar and Eric Haydock's bass, coupled with Elliott's drumming, making up one of the tightest, loudest instrumental ensembles this side of the Who.

Hicks also placed himself in a somewhat conservative light in the same article, separating himself from Keith Richards's comments in the same piece about lessons not being necessary for a would-be guitarist. "Unlike Keith Richard, I do believe in budding guitarists having lessons. I took two years of classical guitar lessons, and I still find them helpful."

In April of that year, The Hollies made their first visit to the United States, a week-long engagement at the Paramount Theater in Brooklyn, on a bill hosted by comic Soupy Sales and starring Little Richard, among others. During this same visit, they also made their first appearance on the network music showcase Hullabaloo.

In May 1965, the band recorded "I'm Alive," a song written by American Clint Ballard Jr., which became their first British chart-topping hit in July, before giving way the Byrds' debut single "Mr. Tambourine Man." In America, by contrast, the song did no better than #107, an embarrassing state of affairs for the band, which it hoped to do something about when it visited the United States in the fall of that year. Stylistically, however, the song showed the group in a much stronger light than its previous singles.

Additionally, during the summer of 1965, the Clarke-Hicks-Nash songwriting team, working as "L. Ransford," achieved what, at the time, seemed like a major breakthrough. The three were signed to a publishing contract by Dick James Music and given their own publishing imprint, Gralto Music (for GRaham, ALlan, and TOny--Clarke: "And when Graham left, it became Alto Music). In songwriting, the prestige of the publishing house with which one signs is a badge of success, much as the status of a record company can be for a recording artist. And in 1965 Dick James was the most important publisher of rock 'n' roll music in England, having signed up John Lennon and Paul McCartney at the outset of their careers and never looked back.

Unfortunately, as Bobby Elliott explained in a recent interview, the terms of the Dick James contract ultimately proved less-than-satisfying. "We were very young at the time, and I don't think anyone was finally happy with what they got. Uncle Dick hadn't looked after us very well at all."

Clarke echoed these sentiments, saying, "It was the same with us as it was with Elton John and a lot of other people during that period. When you're very young, and someone comes to you with an offer of 1000 pounds each as an advance on songwriting, which certainly seemed like a lot of money then--in fact, it was a lot of money--the tendency was to take it."

Still, regrets aside, this era seemed to herald a golden age for memorable original hits by The Hollies, including "Stop Stop Stop," "Pay You Back With Interest," "On A Carousel," "Carrie Anne," "King Midas In Reverse," "Dear Eloise" and "Jennifer Eccles," as well as numerous album tracks of extraordinary beauty. That period, from 1966 thru 1968, saw Clarke, Hicks and Nash become one of the strongest songwriting teams in English rock, capable of holding their own against the likes of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, and Mick Jagger and Keith Richards.

In July 1965, The Hollies announced that they would make their first venture into cabaret, playing both the Princess and Domino Clubs in Manchester on the night of July 30. Their 25-minute sets evidently went over well, with offers of return engagements and favorable coverage in the music press. Cabaret shows were very lucrative, as Nash later observed, although the group subsequently came to avoid doing them because the setting tended to take the edge off of a performance. As Clarke later observed, the audience wasn't as demanding of excitement as a real concert audience, but at the same time the band was often competing with the food and, especially, the alcohol, for the audience's full attention.

In August 1965 they band did a tour of Germany, and then set its sights on America again. Neither their first tour of the United States, nor their record releases in the States had been successful for The Hollies, and the group went over in September 1965 intending to do something about the latter, if at all possible. In addition to Chicago engagements on the same bill with the Supremes and the Animals, they were scheduled to spend a week in New York City for an appearance on the ABC music showcase series Hullabaloo, and, as Hicks described it in the British press at the time, "confront their record company" about the difficulties they'd had selling their music in the United States.

The group's relations with Imperial Records were never very good, according to Elliott. Not only weren't the band's records getting over to the American public, but the executives from the label were less than supportive, somewhat surprising since The Hollies were the only major British pop act on the American label.

"Imperial never gave us much encouragement," recalled Elliott. "I can remember meeting with some fellow over there, in a shiny suit and shiny shoes, who told us we just weren't commercial enough in what we were doing. He listened to Butterfly [the band's mid-1967 psychedelic album] and told us we should try and sound more like the Association."

October saw their new single, the Graham Gouldman-authored "Look Through Any Window," reach #4 in the United Kingdom, while their accompanying album, Hollies, reached #8. For the song's B-side, the group cut a version of Clarke and Nash's very first song, "So Lonely."

For their next single, The Hollies reached out to the Beatles repertory, in the form of George Harrison's "If I Needed Someone," which they cut in November 1965. Recorded at the supposed suggestion of George Martin, the song proved to be the most controversial of the group's early singles: No sooner was it released in December, than Harrison denounced The Hollies' version as "soul-less," and the press attacked the group for allegedly riding on the coattails of the Beatles. As Clarke pointed out in a recent interview, however, he genuinely loved the song, and they did do it differently from the Beatles, especially Elliott's drumming, which was highly complicated and animated.

Additionally, at the time, through a misunderstanding, it was thought that the song wasn't going to be released by the Beatles--at the time that The Hollies' record was cut, the Beatles' own version hadn't surfaced commercially. As a #20 single in England, "If I Needed Someone" was a setback, and an unhappy one, although people who hear The Hollies' version today generally seem to appreciate it.

Their next record, "I Can't Let Go," was a discovery of Tony Hicks's at the offices of Dick James Music, one of two songs that he came away with (the other was John Phillips's "California Dreamin'," which had not yet emerged as a Mamas and the Papas song, which they never cut). Cut on January 13, 1966, "I Can't Let Go" was released the following month and seemingly restored the group's good fortune, rising to #2 in England and #42 in America. "I Can't Let Go" also marked the final appearance on a Hollies single of bassist Eric Haydock.

The group went on a tour of Europe soon after the recording of "I Can't Let Go," including its first appearance in concert in Warsaw, Poland. At the time, Haydock was becoming disaffected from the rest of the band, according to several of those who were present--he had first shown signs of problems on the U.S. tour the previous fall, when he'd resisted remaining in the country to perform amid a problem with the band's work permits.

When The Hollies had returned to England, the band had found him unwilling or unable to perform at various scheduled gigs. Initially they were told that Haydock was having some sort of emotional problems, but then they'd learned that he was out enjoying himself with friends during the evenings that he was supposed to be playing or, barring that, convalescing. At around the same time, Haydock began to raise questions about the way that the group's earnings from its live shows were being handled by its management, and he was out-voted in terms of what, if anything, to do about it.

As it turned out, there was later discovered to be some irregular handling of the band's accounts, and a change was made. By that time, however, it was too late, both from a personal and professional point of view, for any reconciliation between Haydock and the rest of the group.

Haydock had begun fading out of the group before his firing in April 1966, and for a time the band relied on various replacement bassists, including Beatles acquaintance Klaus Voorman, whom they couldn't afford to engage full-time. Jack Bruce even sat in on the May 10 recording session for the movie title-song "After The Fox," with co-author Burt Bacharach at the piano as well.

On May 18, 1966, it was announced that Bernie Calvert (born September 16, 1942), the former bassist with the Dolphins, was The Hollies' new bassist. Calvert's tenure with The Hollies is the subject of some controversy for fans. Many don't consider him to have been a good bass player, at least compared to Haydock, whose playing had a much higher profile on the group's records. Ron Richards seemed to bear this out in his contribution to the notes of Epic Records' 20 Song Anthology, remarking that Calvert was not a good bass player, and that Richards deliberately buried his sound in the mix of their songs once he joined the group.

The group's first major project with its new line-up wasn't a Hollies record at all, but something more unusual. The group had been selected to work on the new album by Clarke and Nash's longtime idols the Everly Brothers, writing new songs and recording behind the duo along with session guitarist Jimmy Page. The resulting album, Two Yanks In England, recorded in the midst of a long fallow period in their history, is generally regarded as the best of the Everly Brothers' long-players of the 1960s prior to Roots.

On May 18, 1966, The Hollies recorded the song that was to become their long-awaited American breakthrough single, "Bus Stop." Written by Graham Gouldman, and featuring an opening that was worked out on stage with help from Klaus Voorman when he was sitting in with the band, "Bus Stop" rose to #5 in America as well as making it to the same spot on the English charts.

By this time, the band had blossomed as songwriters and recording artists. Its next album, For Certain Because, was their most elaborate yet, its songs, all originals, filled with unusual instrumentation, including marimbas, kettle drums and other exotic sounds. In many respects The Hollies' equivalent to the Beatles' Rubber Soul album, For Certain Because was the first album by the group in which not a single track was filler, and on which every track could have been either a proper A-side or B-side of a single. Indeed, one song off of the album, "Pay You Back With Interest," was issued as a single by Imperial in America after the band signed with Epic, while another, "Tell Me To My Face," was later covered very successfully in the 1970s by Dan Fogelberg and Tim Weisberg, and remains in The Hollies' repertory in 1996. Other songs, such as "Clown," were more personal compositions by Graham Nash, who was starting to develop a distinctly individual approach to songwriting.

Some time during 1966, Bobby Elliott also began to develop his art further, recording three solo tracks, part of a suggested larger project that never came to fruition, in conjunction with fellow drummer Bob Henrit of the Roulettes.

This was a golden era for The Hollies as a performing unit as well. In concert, they worked on the same bill with acts such as the Spencer Davis Group and the Small Faces, and their music onstage had achieved a level of sophistication equivalent to the kind of songwriting they were doing.

Their next single, "Stop Stop Stop," was the first Hollies song to feature the sound of a banjo, something that Hicks rather regrets today. "We used it on that record and I've had to carry the banjo around on tour for close to 30 years," he said, jokingly, "because we've never stopped playing it in concert."

The record's success, achieving the #2 spot in England and #7 in America, was all the more remarkable as an original A-side. Their follow-up record, "On A Carousel," was written during the group's tour of America, and recorded on January 11, 1967. Released the following month, it reached a by-now routine #4 in England, and #11 in America.

"Carrie Anne" had been started by Hicks in 1965, while the band was on tour in Norway, and started out in the wake of the Byrds' "Mr. Tambourine Man," with Hicks writing to the phrase "Hey Mr. Man." Two years later, it was finished in its familiar form and recorded on May 3, 1967, in only two takes. Released later the same month, it ascended to #3 in the United Kingdom and #9 in America.

By this time, The Hollies were considered one of the top groups in England, and so successful with their own compositions that Ron Richards and EMI were willing to allow them some new latitude. Additionally, the group, and Graham Nash in particular, was availing itself of all of the new forms of musical and extra-musical indulgence that London allowed them in the spring before the Summer of Love.

After the Beatles released Sergeant Pepper in June 1967, The Hollies decided to try their hand at psychedelic music with a new song, largely written by Nash, called "King Midas In Reverse."

The group's most elaborate recorded work to date, "Midas," which was recorded on August 3 and 4, 1967, was filled with all kinds of sound effects and surprising timbres, a string section that sounded positively unearthly in its density and texture, and a festive mood that made it one of the most cheerful pieces of psychedelia ever issued. It took some persuading to get Ron Richards to release "Midas" as a single, and once it was out, it never did more than brush the charts in England or America, reaching #18 at home and #51 in the States.

Although it was a disappointment for Nash, who liked the song well enough to perform it acoustically during his early years with Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, "Midas" was only a small part of the most beguiling period in The Hollies' history.

The Psychedelic Era

Apart from "King Midas In Reverse," it is probably news to most casual listeners in America that The Hollies ever made a significant contribution to psychedelic music. This is mostly a result of the poor sales of their albums, coupled with the changes that were made in the song line-ups of their long-players upon release in the United States, and the fact that they changed labels immediately prior to releasing this material.

By 1967, leaving Imperial Records was a gilt-edged priority for the band and its management, who by now had realized that the label would never get seriously behind their records. The group's final Imperial single, "On A Carousel," was released in February 1968, and the band's next single, "Carrie Anne," released three months later, marked the start of a 10-year relationship with Epic Records.

"Ron Richards and Harold Davidson engineered our exit from Imperial," Elliott remembered. "It happened after Imperial rejected Butterfly as not commercial enough. We were happier with Epic, because they took a much more active interest in promoting the records--they were a larger company also, and that was a help."

In June 1967, Epic Records released a 10-song version of Evolution, shorn of "When Your Light's Turned On," "Leave Me" and "Water On the Brain," but with "Carrie Anne" added. The album never charted, but "Carrie Anne" did reached #9, a fair achievement at the time and one of the group's better showings in the U.S., only "Bus Stop" and "Stop Stop Stop" having done better.

The year 1967 saw the band release not one, but two long-players, Evolution and Butterfly, that can only be regarded as classics of the psychedelic era. Either record can command a place alongside the Beatles' Revolver or Sergeant Pepper, or even that Pink Floyd standard, Piper At The Gates of Dawn. To date, however, only hard-core Hollies fans have ever picked up on either album, a genuine tragedy for those who are missing them.

Evolution is probably the equal of the best psychedelic album ever recorded by any band. Released in June 1967, just as the Beatles' Sergeant Pepper album was sweeping the media and the public, Evolution was a 12-song classic in its own right. It has its weird, spaced-out side, embodied in songs like "Water On the Brain," and material ("Ye Olde Toffee Shoppe") dressed up in the obligatory tinkling harpsichords and tremolo effects, as well as softly sung ditties ("Stop Right There") about druggy, romantic states of mind.

But it also has balls, something most psychedelic albums were missing in their quest to depict the next level of cosmic consciousness. In the course of writing drug songs, The Hollies never gave up their core purpose as a performing band. Anyone who loves Beatles' songs like "Fixing A Hole" for its loud guitar break may well melt over "Then The Heartaches Begin," "When Your Light's Turned On" or "Have You Ever Loved Somebody," the latter a Clarke-Hicks-Nash original that is, unfortunately, better known for the smoother, poppier version done by the Searchers as a single.

Allan Clarke was largely responsible for both the album opener, "Then the Heartaches Begin," as well as "Have You Ever Loved Somebody," the two best hard rock songs on the album. Of "Have You Ever Loved Somebody," he admits, "I rather liked the Searchers' version. I felt they should have had a hit with it."

Tony Hicks's searing guitar on "Have You Ever Loved Somebody" leaves no doubt that these guys were still a rock 'n' roll band, and presents Hicks's single guitar sound to better advantage than any other records by the band--this is what psychedelic music played by his much-idolized Pirates might've sounded like.

Even "You Need Love," a rather urgent love-song with a radiant chorus built around the title phrase and embellished with brass flourishes, is credible rock 'n' roll. "Lullaby To Tim" anticipates the tremolo-vocal effect later used to great effect by Bill Wyman on "In Another Land" from the Rolling Stones' album Their Satanic Majesties' Request, except that the song has a better melody and more intelligible lyrics; it also anticipates "Lady Of The Island" from Nash's "Lady Of The Island" from the first Crosby, Stills and Nash album. And "Rain On the Window" seemed to deliberately recall "Bus Stop," embellished with beautiful horns, while the basic acoustic guitar track drives the piece along.

On song from the group's psychedelic era that Clarke would like to forget is "Water On The Brain," a number from the British LP Evolution that has only appeared of "King Midas In Reverse." A weird, spaced out number with a frantic, bongo-laden opening, strange tempo changes, a flugelhorn played over the break, and a bizarre chorus of "Drip, drip, it's driving me wild," the song is a kind of cult classic among hard-core Hollies fans, but at the time it got the band a lot of critical mail.

"I'd like to forget that," Clarke explained. "Water on the brain is a disease that can be fatal, and we got a lot of angry mail from people upset that we could name a song after a disease like that. I actually wrote it because of an experience when I was staying at this hotel in Germany, and there was this leaky pipe and a drip that was driving me mad."

The band's next album, Butterfly, was even better, a venture into psychedelia on a more sophisticated level. Released in November 1967, it was clearly done in the wake of the explosion in druggy ambiance heralded by the Sergeant Pepper album and its success. Opening with "Dear Eloise," which was never a single in England, the record ran through myriad psychedelic, trippy, spacey, generally upbeat numbers. Some of the album's songs, such as "Away Away Away," with its flute and horn section arranged by Johnny Scott, or "Wishyouawish," were pure pop that simply fit into the mood and sound of the times, while other tracks, such as the sitar-laden "Maker," were unique creations of their period. "Maker" holds up about as well as any song of the era built around sitars and the process of meditation, with a catchy, poppy middle chorus that took it more into typical Hollies territory. "Would You Believe" was a love song, strongly reminiscent of "King Midas In Reverse" (with the same kind of dense string backing), decked out in bells and lots of echo on the vocals, but lacking the single's beat or memorable choruses.

One song that didn't make it onto the American release of Butterfly, rather awkwardly titled Dear Eloise/King Midas In Reverse (with the latter single added on) was Tony Hicks's "Pegasus," a thoroughly beguiling, hauntingly beautiful composition, that could easily be a drug song masquerading as a lullaby, or which could just as easily be another "Puff The Magic Dragon," a perfectly innocent song that is easily misinterpreted. The chorus featured what could be either a saxophone played backward, a la the Beatles' "Baby You're A Rich Man," or a Mellotron--it is difficult to tell amid the layers of production and overdubbing (but, then, that's half the fun of most of the best records made during this period).

Graham Nash's "Postcard" is proof that less is more, and really should have been a single, a driving love song with a bunch of memorable hooks, gently harmonized and featuring a stripped-down sound compared to the rest of the record, nothing but acoustic guitar, drums and bass, with a few unobtrusive sound effects and a celesta coming in at the end. "Charlie And Fred" was one of those weird songs of eccentrics that every British band used to have at least one of during the psychedelic era--Cream had "Pressed Rat And Warthog" and Pink Floyd had "Arnold Layne"--with a memorable middle verse ("He lived all alone in a hovel ... " ) and a lovely acappella final chorus.

"Try It," written by Allan Clarke, has remained somewhat familiar to American listeners by virtue of its having been included on several compilations, as the B-side of "Jennifer Eccles" in America, it is one of a relative handful of Hollies tracks from the period that Epic Records has held onto in the United States. This was The Hollies' attempt to do a pure psychedelic ode, embellished with lots of tape loops and sound effects.

"Yes, 'Try It' was mine," Clarke recalled. "I was always the member of the band into experimenting with astral projection, meditation and that sort of thing. We all got into the psychedelic scene--Tony was playing a sitar. Not a Ravi Shankar-type sitar, but an electric sitar."

Amazingly, it works, though it is as much of a period piece as any other example of psychedelia from this era. "Elevated Observations?" was a somewhat ironic ode to the joys of psychedelic experience, even featuring the line "Ego is dead" in its chorus--somehow, when The Hollies sang "It's so high up I touch the sky," the latter reference lacked the urgency of Jimi Hendrix's use of the phrase, but the song was quite pretty. "Step Inside" was a love song, whose upbeat, glowing, radiant vocals and mood were contrasted with the offer of "tea and crumpets" to the lady being wooed, a lovely song, that even today, seems to recall the conundrum about British pop-rock of the era once offered up in the pages of Rolling Stone (talking of the Rolling Stones' "She's A Rainbow," and the line "She comes in colors," some wag commented that when Donovan used the word "come," you knew it was for tea…).

And then there was "Butterfly," the most sublimely beautiful record that Nash ever recorded with The Hollies. A song of lost love and fading beauty, embellished with flutes, a full string section, and horns.

A haunting love song sung by Nash alone, "Butterfly" was resplendent in a set of images that, to this listener, at least, recall the opening sections of "Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds" in a favorable way. The song was doubly enticing because it became part of The Hollies' concert set in late 1967.

The allure of The Hollies' psychedelic period was enhanced by the fact that, unlike the Beatles, who ceased touring at roughly the time they started moving into this side of their repertory, or the Rolling Stones, who were off the road for most of the 1967 and 1968, when they might've actually done a song or two from Satanic Majesties, The Hollies remained a working rock band, and chose to integrate their psychedelic repertory into their stage performances.

"We would go out on the road and use the taped orchestral accompaniment from the record," Elliott recalled, referring to "Butterfly." "We'd sing and play to that. A lot of people don't realize that we had a whole set of backup musicians for those shows, string players that we would recruit locally, so we could do the material from the records of that period live."

For larger, more centralized gigs, the band was supported by the Mike Vickers Orchestra. A May 25, 1968 review of such a show, from a mid-May 1968 at Shrewsbury, on a bill with the Scaffold and Paul Jones, cited the presence of the orchestra, along with back-projected clouds, during "Butterfly." Other songs in the group's set that night included "On A Carousel," "King Midas In Reverse," "Carrie Anne," and covers of Bob Dylan's "Blowing In the Wind" and "The Times They Are A-Changin'."

As Elliott pointed out, "Everybody was doing that sort of thing at the time, and so were we."

As to how well the group really took to psychedelic music, Allan Clarke remarked, "The kaftans and the bells, and the sitars--Graham was really at home with all of that, more than the rest of us."

Nash's enthusiasm for the changes taking place in the music scene was matched by his appreciation for many of the extra-musical diversions of the era. While virtually everyone working on the pop music scene was exposed to the drug culture during this era, Clarke, Hicks, Calvert and Elliott preferred the more mundane indulgence of a pint at the local pub to the more exotic chemical intoxicants in which Nash began to partake ever more regularly.

"We used to spend a lot of time at clubs like the Adlib, and UFO and the Bag O' Nails," remembered Clarke of the era from 1966 through 1968, "and it was one big party. Graham was much more into all of it, partly because he was splitting up with his wife, and busy finding out who he was. I was married, and settled in that way, and already knew who I was."

Additionally, Nash's attitude toward music was changing very rapidly. The songwriting team of Clarke-Hicks-Nash existed officially on paper, but it was becoming clear that Nash's work was becoming more personal in ways that the rest of the group did not care to share. Where Clarke and Hicks were content to write straight-ahead rock 'n' roll if the mood so struck them, Nash was looking for more outré and experimental subjects, and wanted to write songs that had meaning. Additionally, Nash was starting to chafe under The Hollies' continued image as a pop band, with a following centered on their singles and on younger listeners.

Gradually, Nash was becoming closer to a couple of California-based musicians, Stephen Stills and David Crosby, whose acquaintance he'd made, and he began to do demos of his songs with them. No one in The Hollies seemed to mind.

"He played us the demos he made with Stephen and David," Elliott remembered in a recent interview, recalling the developing split between Nash and the others, "and we didn't mind, we thought they were great. We had no problem with it."

The Hollies had given him room for his own songs ever since "Fifi The Flea" back in 1965; during 1968, they'd even tried to record "Marrakesh Express," the song by which Nash later introduced himself, reconstituted from pop band member into a singer-songwriter, to a huge public on the first Crosby, Stills and Nash album, and on a single by the trio.

"Oh, yeah, we did try to do 'Marrakesh Express,'" recalled Elliott, the band's semi-official in-house archivist and historian, "but we could never get it right, so we never released it. The tape still exists, but we never really finished it."

"Graham had reached a point," explained Clarke, "where he wanted separate credit for the songs that he wrote, instead of having everything credited to Clarke, Hicks, and Nash."

Finally, in November 1968, following the group's return from a tour of Europe, it was announced that The Hollies would postpone a scheduled American tour. A few days later, it was announced that Graham Nash was leaving The Hollies.

For The Hollies, the departure of Nash wasn't as big a crisis as, say, Paul McCartney's quitting was a problem for the Beatles. On the other hand, his exit was a good deal more important than the departure of a member who only played rhythm guitar. In fact, Nash had done relatively little of that, but his voice and his songwriting had made a significant contribution to the group's success.

A lot of bands and musicians were sorting themselves out in 1968 and 1969. By that time, none of the Beatles (except Ringo) was exactly crazy about spending much of their time and energy acting as session men on the other members' songs, and McCartney was less than enthused about having the Lennon-McCartney contractual partnership survive into the era of John Lennon's political songs, much less the even more personal primal-scream-therapy-based compositions that were to come from Lennon. Steve Marriott, weary of the Small Faces' teeny-bopper appeal, exited his band at the end of 1968; and the Yardbirds, after numerous personnel changes over the preceding three years, split up in the spring of 1968 along a fault line dividing Jimmy Page and Chris Dreja's desire to get on with the business of playing blues-based rock 'n' roll from Keith Relf and Jim McCarty's embrace of psychedelia and the counter-culture.

The difference for The Hollies--and one that speaks volumes about the sheer talent within the ranks of the group, and their loyalty to each other--was that, when the split with Nash came, the group survived intact and thrived, even as Nash successfully reinvented himself as a third of Crosby, Stills and Nash, and later as a solo artist.

These differences came to a head in a series of events in the middle and end of 1968. Nash's frustration was only increased by the success of the single "Jennifer Eccles," which he and Clarke had authored as an almost deliberately superficial pop song.

"That was our way of getting back to our audience, after 'Midas,'" explained Elliott. "We'd missed the mark, and we were trying to find it again."

And they did, with the new single reaching #7 in England and #40 in America.

For many years, the story has circulated that the final straw for Nash was the group's decision to do an album of covers of Bob Dylan songs. But Nash participated in performances of Dylan songs by the group onstage during late 1968, and was involved in the early stages of planning the Dylan album.

In any case, Nash's final project with the band was an obligatory appearance at a benefit concert at the London Palladium in late December 1968.

Regrouping The Group

The Hollies recruited Terry Sylvester (born January 8, 1945), an ex-member of the Swinging' Blue Jeans and the Escorts, to replace Nash. Sylvester was not the same kind of songwriter as Nash, although each of them, curiously, evolved separately into mellow singer/songwriters during the 1970s (that is, when Nash wasn't writing topical songs).

The Hollies recruited Terry Sylvester (born January 8, 1945), an ex-member of the Swinging' Blue Jeans and the Escorts, to replace Nash. Sylvester was not the same kind of songwriter as Nash, although each of them, curiously, evolved separately into mellow singer/songwriters during the 1970s (that is, when Nash wasn't writing topical songs).

In February 1968, following his debut with the band at Cardiff University, Sylvester participated in his first recording session with The Hollies, on the stopgap single "Sorry Suzanne," which reached #3 in England that spring. The Hollies Sing Dylan album, also released in the spring of 1968, reached #3 on the English charts in June 1968, but generated a massive amount of controversy in America, where the newly constituted underground rock press, principally embodied by Rolling Stone and a handful of other magazines, savagely attacked the entire notion of the record, as well as its execution.

In reality, there were some inspired moments on the album. "When The Ship Comes In" and "My Back Pages," in particular, were very nicely executed. The main problem was that the rock press, speaking for what could be presumed to be the majority of Bob Dylan's audience, saw no compelling reason for anyone doing Hollies-style covers of Dylan's songs.

The Hollies were hardly limping along with sales success of that kind. In America, despite the controversy that it generated, the Dylan album managed to stay in print for many years into the 1970s, no small feat for a band whose records were routinely deleted after a year or two. But the band still needed to come up with a new batch of songs, and this time without Nash, who, despite his increasingly individualistic voice, had been a key creative member of the group.

Their November 1969 album, Hollies Sing Hollies, failed to chart, but that was a relatively small matter, as it turned out. The previous spring, Hicks had discovered a song among a group of publisher's demos that he immediately brought to the attention of the band as a likely hit, "He Ain't Heavy, He's My Brother."

The song, a topical, serious, dramatic number, was quite unlike anything else the group had ever released as a single, but it seemed to be what they were looking for. As with every other single that they had ever done, it didn't look backward to their immediately past work, and it seemed to offer the group, and especially Allan Clarke, the chance to excel at what it did best. The only thing it ultimately didn't have, amid its beautiful arrangement for voices and stripped-down band (including piano by Elton John)--and this shows some of Hicks's selflessness--was a part for a guitar, the first such record The Hollies had ever done.

The song, a topical, serious, dramatic number, was quite unlike anything else the group had ever released as a single, but it seemed to be what they were looking for. As with every other single that they had ever done, it didn't look backward to their immediately past work, and it seemed to offer the group, and especially Allan Clarke, the chance to excel at what it did best. The only thing it ultimately didn't have, amid its beautiful arrangement for voices and stripped-down band (including piano by Elton John)--and this shows some of Hicks's selflessness--was a part for a guitar, the first such record The Hollies had ever done.

The song, cut in June and August 1969 and released in September--the title of which, incidentally, comes from an inscription at the gates of Boys Town--hit #3 in England and #7 in America, and racked up the highest sales the band ever had. Indeed, it became to The Hollies something like what "Nights In White Satin" became to the Moody Blues, an internationally known signature tune that, periodically re-released, tended to shoot to the top of the charts every decade or so. In fact, "He Ain't Heavy" would be reissued 19 years later and achieve the #1 spot in England.

The Hollies now seemed to be riding higher than ever, although to read the rock press, one would still have thought that, in the wake of Nash's exit, the group was struggling along. In fact, Nash had achieved a great deal of respectability in the late 1960s and early 1970s as a member of Crosby, Stills and Nash (and Young), and the rock press was quick to embrace the political-correctness of his music's views on the war and other issues. In the process, the tendency was to debunk the group that he had come out of--this was especially easy in the case of The Hollies, who were, after all a pop-rock outfit.

It was all a matter of where one's perspective was in late 1969: In August 1969, while The Hollies were putting the finishing touches on "He Ain't Heavy," Nash was appearing with Crosby, Stills and Young at Woodstock.

One could visualize how the Byrds, David Crosby's former band, in a different reality, would've fit in at Woodstock, or how Stephen Stills and Neil Young's former band, the Buffalo Springfield, could've played the festival if it had stayed together. But no one could visualize The Hollies playing to the Woodstock generation, much less playing the festival. And there was Graham Nash afterward, helping to make a hit out of Joni Mitchell's song about the festival.

The 1970s: More Hits, More Changes

While Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young attracted the attention of the press and public seemingly without effort, The Hollies soldiered on selling records but, curiously, unable to achieve any lasting respect from the press.

Part of the problem for the group was that its business was mostly about playing music, not spouting politics, or any other extra-musical activities. When Clarke, Hicks, Sylvester, Calvert and Elliott weren't performing or recording together, they were engaged in genuinely private lives, with families and personal responsibilities, and they didn't do anything worth writing about. Coupled with the fact that their records didn't really have an underlying philosophy, other than that they were well crafted, superbly played and often very popular, it made The Hollies almost an anachronism in the 1970s: no drug busts, car or motorcycle accidents, messy lawsuits, affairs with movie stars or politics. And to top it off, they still did their best work on 45 RPM singles, a format that was diminishing in importance, at least as far as the rock press was concerned, on an almost daily basis.

"He Ain't Heavy" was as serious as The Hollies ever got, and it even received the begrudging blessing of Rolling Stone in a review (in those days, singles still got reviewed). It put a lie to the perceived lightness of the band--it wasn't exactly "Ohio," but it helped The Hollies maintain a credibility beyond the singles charts.

Musically, they were probably better than Paul McCartney's Wings, which would be filling arenas all over the world by the mid-1970s, but in terms of image, The Hollies were lumped by the press alongside acts like Bread, or, ironically enough (given the comment of that Imperial Records executive back in 1967), the Association: human jukeboxes, playing pop hits that were great ambient music.

"He Ain't Heavy, He's My Brother" had been a gift from heaven, especially as the albums that the group was working on were ignored by the public on either side of the Atlantic. Otherwise, however, the critics--and, more importantly, the all-powerful editors who controlled what got into print--thought of The Hollies as not much more relevant than, say, Gerry and the Pacemakers would have seemed in 1971, except that The Hollies happened to still be making music, and happened to have grown.

There were changes during this period. In the wake of Graham Nash's departure, the official Clarke-Hicks-Nash songwriting team was dissolved. After playing out a few of the old trio's copyrights and some attempts at continuing to work together, Hicks began writing songs in collaboration with his singer friend Kenny Lynch, while Clarke began working with a couple of friends of his, Roger Cook and Roger Greenaway, and Terry Sylvester also began writing songs on his own. The band also began to play longer sets onstage, which meant that Sylvester began playing more.

"In the early days," Hicks observed early this year, "Terry Sylvester really didn't play much guitar onstage, but as our sets began to get longer in the 1970s, he did plug in, because then we needed the second guitar."

The group had finally seemed to stabilize when the biggest crisis of its history loomed early in 1971.

In March of that year, The Hollies released a new single, "Hey Willie," co-authored by Allan Clarke and his friends Cook and Greenaway. This record had a heavier sound than anything the group had ever released on a single before, opening with a loud, crunchy guitar sound closer in spirit to Status Quo, or even the Who, than to The Hollies. The B-side, "Row The Boat Together," written by Clarke alone, was closer in spirit to The Hollies' more usual sound. Though nobody would have guessed it at the time, the collaboration between Clarke, Cook and Greenaway pointed in new directions for all concerned: "Hey Willy's" driving guitar opening was the precursor to a song that would become one of the band's two signature tunes for the 1970s, and bring it more recognition, as well as more problems taking advantage of its success, than anything they'd done in two years. And it pointed in a direction that Allan Clarke was planning on taking his career.

For nearly a decade, Clarke had been a professional musician, and had reached the point where he wanted to step out and begin a solo career. He had been locked into the group identity for nearly all of his adult life, and now felt the urge to step out on his own. The group was beginning a work on a new album, which Clarke would do with them, after which he would begin work on his own career and his own recordings, independent of the band.

Ironically, the new album was to benefit from Clarke's plans for a solo career, but the group's ability to take advantage of its unexpected success was to be sorely tested. While recording the album, titled Distant Light, Clarke turned up with a song that was to be added to the record: a throwaway, co-authored by Clarke, Cook and Greenaway, titled "Long Cool Woman (In A Black Dress)."

Recorded on a day when producer Ron Richards (who later mixed it) was absent, the album gave Clarke a rare chance to show off his guitar skills.

"Normally, when you have Tony Hicks on hand you don't need anyone else on guitar, but that happened because I devised the riff, so I got to play it," Clarke recalled in a 1996 interview with the author. "The song was born in the basement of AIR Studios, and it made the album."

The problem was that Clarke had not intended it to be released on a Hollies album, but as a record of his own. A couple of members of the group did play on it, however, and he was forced to include it on Distant Light.

This, in turn, led to an open breach between Clarke and the rest of the group, once they learned that he intended to do a solo recording. Clarke was issued an ultimatum, that he either remain with The Hollies or pursue a solo career, but not both. Clarke chose to leave.

"They thought that when I became successful, I'd leave them anyway, so they just shortened the agony by forcing me to do one thing or the other," Clarke later recalled, in a 1973 interview with Melody Maker. "It was silly, really, because I wouldn't have left the group."

Silly was putting it mildly. Suicidal was closer to the mark, and unbelievably awkward as well, when "Long Cool Woman" came out as a single and suddenly became the group's new signature tune, saturating the airwaves in the United States.

Ironically, the record had never been intended as a single, possibly because it was not representative of the album as a whole or the group's sound at the time. But when EMI's German subsidiary spun it off as a 45--German audiences finding this piece of quintessential American-style rock 'n' roll absolutely irresistible--the American and British divisions decided not to hold back. Distant Light was released in England by EMI in June 1971, and in December of the same year by Epic Records in America. By that time, Clarke was long out of the group, a fact scarcely recognized by most Americans, given the group's relatively low profile in the rock press.